Post-Famine diet

In 1840, Samuel Lewis wrote of the Irish diet: ‘The general food is potatoes and oaten bread, sometimes with buttermilk or fish; butchers meat is only used at Easter and Christmas, or on other great festive occasions.’

Those of the labouring class were most affected by the Great Famine of the late 1840s. They had nothing. The poorest labourers and small tenant families lived on a monotonous diet of potatoes and milk, relieved occasionally by turnips or bacon. They existed season to season in tiny mud cabins on a patch of land that they leased under a system called ‘conacre’. Under conacre, they were given a plot for a single season in exchange for casual labour and/or rent. They used the plot to grow enough potatoes to feed themselves and to keep a pig. Even when they got paid work, a labourer would often not make enough to feed his family or pay the rent, and the pig was frequently sold to meet his debts.

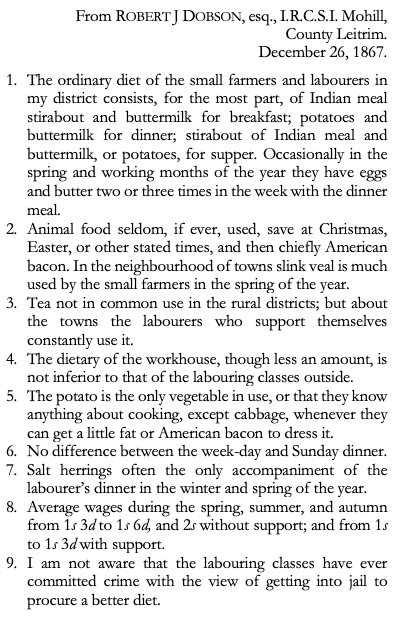

After the Famine, the diet eaten by ordinary people gradually became more varied as more foods became more commonly available and affordable. In 1867, the medical officer for Mohill, Robert J. Dobson documented the local diet as part of a parliamentary enquiry into the ‘Dietaries of County and Borough Gaols in Ireland’. He wrote that most people in the area ate three meals a day, each comprising some combination of stirabout (porridge) made from Indian meal, potatoes and buttermilk. This might be augmented in spring and ‘working months’ with eggs and butter for the evening meal; the only vegetable was cabbage, and there was little meat except for American bacon on rare occasions; slink veal ‘was very much used’ by small farmers during springtime, and salt herring was eaten in winter and spring. Dr Dobson noted that the workhouse diet was ‘less an amount’, but ‘not inferior’ to that outside, and he was ‘not aware that the labouring classes have ever committed crime with the view of getting into jail to procure a better diet’.

Effectively, potatoes remained the main food for many; they were eaten communally out of a basket with many families sharing a single ‘noggin’, a deep wooden ladle filled with buttermilk for dipping the potatoes. In County Leitrim, the significance of such utensils is reflected in local folklore and a saying that when a person died, ‘there is a noggin and a spoon for another’.

While the diet of poorer people in the area remained very limited, people gradually gained access to a greater range of foods as affordable foodstuffs became available in the shops in Mohill. Some of the middle-class farmers grew a wider range of vegetables, and the Mohill Agricultural Show, and later Lough Rynn Cottage Garden Show, became annual events at which local middle-class women and men showcased a range of vegetables including marrow, beans, peas, cabbages, carrots, Jerusalem artichokes and apples. There were also prizes for flowers and household plants, as well as home baking, honey and butter; women presented a range of craft work with prizes for needlework, knitting, and ‘fancy work’ on items such as slippers, gloves, socks, chemises and babies’ hoods.

This was still a world away from the lifestyle of the gentry and upper-middle classes whose gardens might include greenhouses and a tennis court, and who had access to a broad range of home-grown and imported foods. The greenhouses at Lough Rynn were designed to allow a range of fruit and vegetables to be grown, and two notebooks include recipes for Indian curry, fried oysters and macaroni, and list ingredients such as parmesan cheese, lemons, and spices like nutmeg and cloves (see Recipes & Remedies of Lough Rynn for more).

Kate Cullen, wife of Michael Mitchell, the bank manager in Carrick-on-Shannon in the late 1850s, recounted how her husband would send her game, pears and lobsters when she was away in County Sligo. At gentry dinners, the menus were elaborate and the food was extravagant. Cullen saved the menu from the annual Grand Jury Summer Assizes dinner of 14 July 1856 which was held at the Court House in Carrick-on-Shannon and prepared by the ‘cuiseniere’, Mrs Hall: guests were served over thirty separate dishes, including ‘Fricondeau of Veal with Tomato Sauce’, ‘Lobster Paties’ (sic), ‘Mock Turtle Soup’, and ‘Almond Cheesecakes’.

All content written by Fiona Slevin, unless otherwise stated. © Fiona Slevin | All rights reserved: please do not use, copy or reproduce without prior permission or citation. Notwithstanding CC Licence below, content not to be used for commercial purposes. | Last updated February 2025

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.