Lord Leitrim assassinated

Lord Leitrim assassinated

Part of a series of articles published in the Leitrim Observer in summer 2020.

'1870: a Society in Transition' looked at the Ireland of 150 years ago as it emerged from the Great Famine.

Part of a series of articles published in the Leitrim Observer in summer 2020.

'1870: a Society in Transition' looked at the Ireland of 150 years ago as it emerged from the Great Famine.

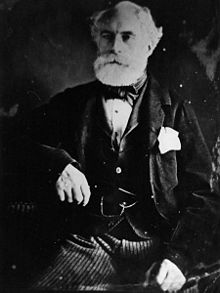

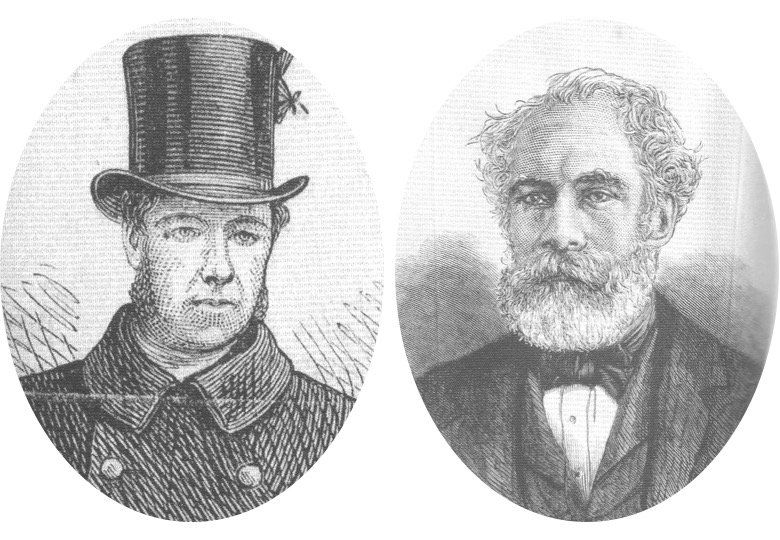

William Sydney Clements, 3rd Earl of Leitrim was a key figure in Leitrim and Irish life during and after the Famine. In 1878, at 72 years of age, Lord Leitrim was still physically strong and very much in charge of the management of his estates. From the end of the 1860s, he spent most of his time in Donegal in an effort to quell local resistance to his increasingly harsh and wholesale evictions

Escalating resistance

Escalating resistance

The locals had seen some success in forcing Lord Leitrim to turn empty farms into pasture, since few new tenants would take on an evicted farm. But there was increasing anger about the increasing scale and severity of the clearances. In March 1876, there was outrage over a series of evictions during a particularly cold spell. A Presbyterian widow named Algoe was evicted with her six young children, together with three cottier families, apparently because they had cut some trees. Three days later, six more were evicted, allegedly for gathering seaweed or cutting turf. Their dwellings were levelled by up to twenty bailiffs protected by twenty armed police. One newspaper reported how ‘old and infirm persons, women and children, were put out in the snow on the mountain side, absolutely without shelter’.

Things continued to escalate, and in early 1878 there were reports that eighty evictions were planned in the Fanad area. By then, the earl was a ‘marked man’ and he had taken to travelling heavily armed and with a strong escort.

Ambushed

Ambushed

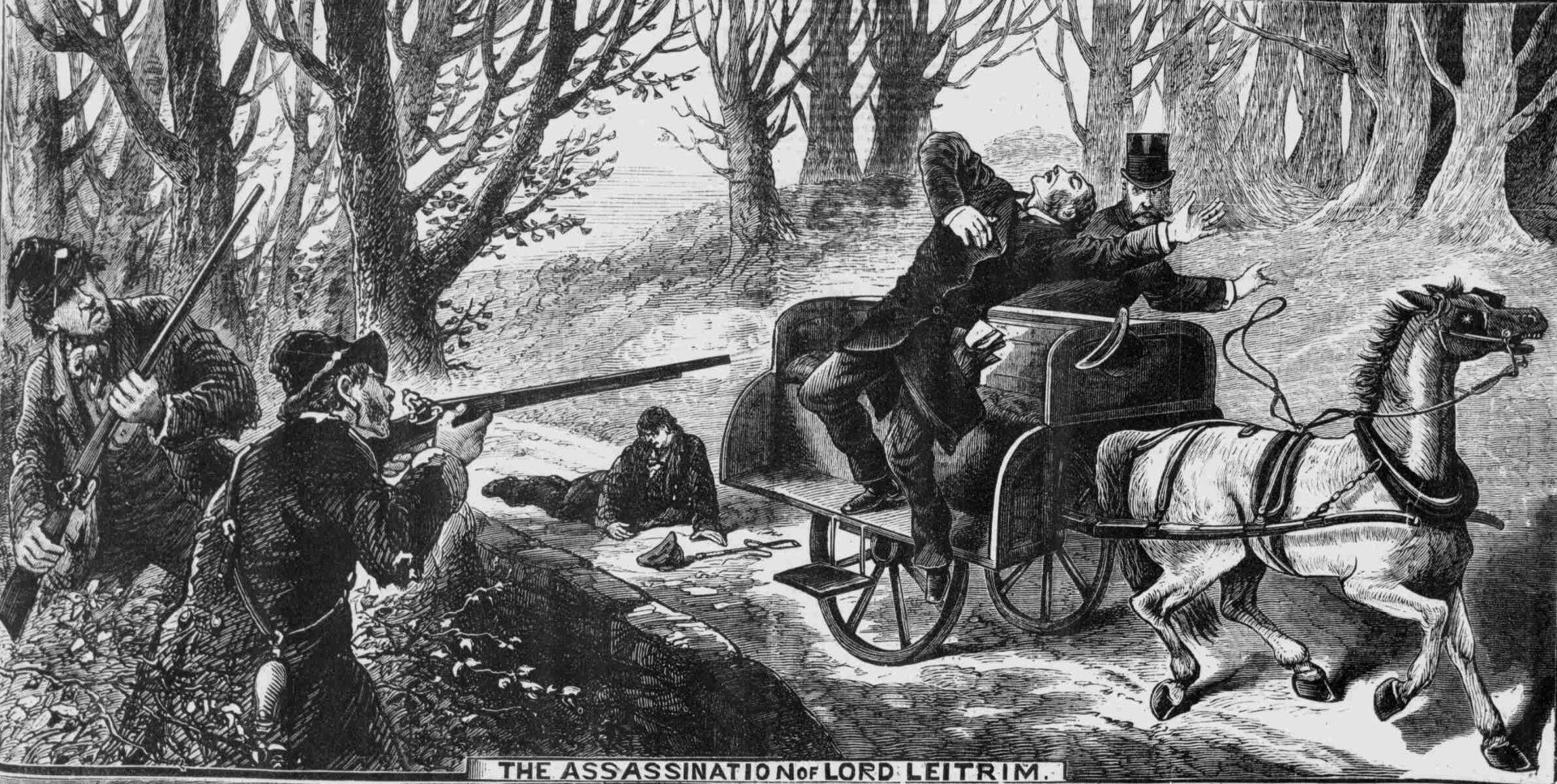

On the morning of Tuesday 2 April 1878, he set out from his house at Manorvaughn, timed to arrive at Milford by nine o’clock. There were two carriages: the first was the Milford Hotel coach carrying Lord Leitrim, the Court Clerk, John Makim, and a young coachman, Charles Buchanan; the second car held Lord Leitrim’s coachman and valet (and probable son), William Kincaid, and Michael Logue, the owner and driver of the car. In truth the party had left an hour early, which may explain the absence of his normal police escort. It was said later that the clocks in Manorvaughn had been deliberately set back.

The morning was cold with driving sleet and a biting wind. By the time the party reached Woodquarter near Cratlagh Wood, the carriages had slowed to take a steep hill. Lord Leitrim’s car went ahead, while Logue and Kincaid’s car trudged some two hundred meters behind.

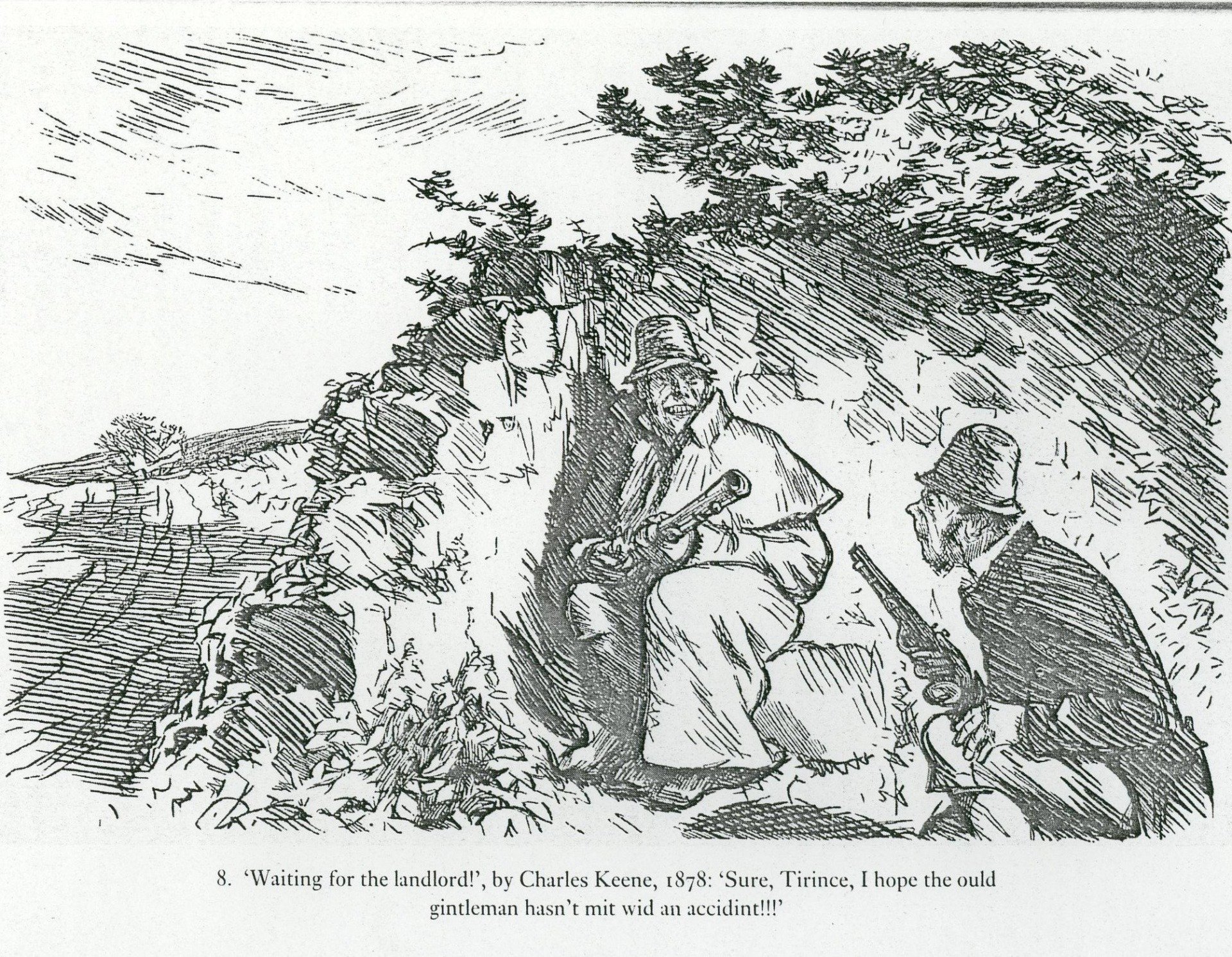

Waiting patiently at the scene were two local men, Michael McElwee and Neil Sheils. They had taken their position at seven o’clock and lay in wait for Lord Leitrim’s party. Another man, Michael Heraghty, had arrived with them but had left the scene (and his gun) to ensure that a passing pedestrian didn’t warn the authorities of their presence. McElwee and Sheils remained, and awaited their target.

The first volley of shots hit the coachman, Charles Buchanan, in the head. He died immediately, falling to the road, his rug still around his knees. John Makim, the clerk, was also shot in the head but managed to stumble back towards the second car. He died later. Lord Leitrim never got to either of the two weapons he had with him. One of the first shots hit him in the right arm, fracturing his elbow, and he took nine or ten bullets in the back of his left shoulder. The horses panicked, throwing the earl to the ground.

McElwee and Shiels approached, but the earl managed to get to his feet and wrestle with the two men. When he was found later, he was still clutching a portion of a red beard which could only have belonged to McElwee. The struggle was short, and ended when Shiels struck Lord Leitrim with the gun in a blow that was violent enough to split the gunstock. The earl fell face down in a pool of water at the side of the road. His new hat was found nearby, unsoiled and unbattered. His black bag, full of money and containing his fine revolver, was left intact and recovered later.

The entire episode lasted some ten minutes. Shiels and McElwee ran the seventy paces to the shores of Mulroy Bay to a waiting boat, and Kincaid watched from the second car as they rowed hurriedly from the shore and crossed the bay. Kincaid then drove on to Milford and alerted the police.

There was little doubt among the tenantry about who the actual assassins were, but no one informed the authorities. Immediately after the murder, each of the conspirators went back about their daily business. McElwee was to be seen soon afterwards constructing lobster pots and Shiels went back to his tailor shop. Heraghty went to the house of some friends where he had a meal of tea and eggs.

In the end, Heraghty was the only one to be arrested: the broken gunstock was the only usable evidence and its ownership was traced to Heraghty, but He appeared at Lifford Assizes on 19 July 1878. He was described as being about twenty years of age, small and wiry with black hair, light grey eyes and a low forehead. On the day of his trial, he was ‘sallow and ill-looking’. He died in gaol three months later from typhus and without being convicted of the crime.

Of the three men ultimately attributed with Lord Leitrim’s murder, two died before they could come to trial; the third, McElwee, was never apprehended and continued his career as a travelling tailor until his death in 1921.

Inquest

Inquest

After his assassination at Cratlagh Wood on 2 April 1878, Lord Leitrim’s body was taken to Milford for inquest, along with that of John Makim, the court clerk who had also been killed in the ambush. The bodies were laid out in a narrow chamber with bare whitewashed walls on plain deal tables. The contrast between the two men in death was marked. Makim was surrounded by friends ‘expressing their wild grief and singing praises and prayers’, while his ‘unhappy master’, for all his wealth and status, lay alone, ‘without a single circumstance of dignity’.

Robert Clements, the earl’s nephew and prospective heir, was in Paris when he got word of the murders. He set off immediately for Donegal where he waited until 8 April when Lord Leitrim’s body was released for removal. Robert accompanied the body on the long journey from Milford back to Killadoon, travelling via Letterkenny and Strabane, and onwards by rail to Dublin.

Unruly scenes

Unruly scenes

On 10 April, the funeral cortège made its way from Killadoon to Dublin for internment at St Michan’s church. By the time the mourners reached the city, word had spread of the earl’s death, and groups of hecklers hurled abuse at the coffin as it passed along the Liffey. At half-past two, the procession reached the bottom of Church Street. The Times reported the disorderly scene as the chief mourners and gentry ‘were charged and literally hurled back from its vicinity’. The hearse was surrounded by a large mob who ‘shouted, cheered, hissed, and threatened’ and ‘made to open the door of the hearse, and get at the remains’. This went on for twenty minutes, with the police unable to impose any order until twenty-five policemen arrived. Even then, the police and mob clashed several times before the undertakers were finally able to remove the coffin.

Robert Clements and John Ynyr Burges, Lord Leitrim’s brother-in-law, were astounded at the size and anger of the mob, which continued shouting and cheering even through the burial service. In the end, Robert Clements feared the crowd so much that he alone accompanied the coffin as it was interred in the family vault inside the church. After the service, Robert and the chief mourners had to be escorted out by a seldom-used back gate.

Rewards for information

Rewards for information

Various rewards were offered for the identification of Lord Leitrim’s killers. The heir to the earldom, Robert Clements, was reported as offering £10,000. A group of thirty magistrates raised £6,000 from a few allies. The government offered a £500 reward, though required information to be submitted within six months – not a great indication of any enthusiasm to apprehend the assassins. Officially, no information was forthcoming, and the rewards went unclaimed. In the 1960s, it emerged that information had, in fact, been gained by the Lord Lieutenant’s agent (for 17 shillings), but had been filed away in Dublin Castle and ignored.

Unlamented

Unlamented

The truth was, in the decades after his death, Lord Leitrim was neither mourned by his tenants nor defended by his peers. The earl’s killers were lauded locally as heroes who ended the tyranny of landlordism in Ireland. Back at Lough Rynn, few, if any, expressions of regret were received from tenants on smallholdings, though the Castle did receive letters of regret from some of the earl’s larger leaseholders. The Orange Lodge in Mohill, meeting in the town’s courthouse, declared that its members ‘sing the praises of Lord Leitrim, and proclaim to the world that he was a chaste God-fearing man and a kind indulgent landlord and that anyone who would say otherwise are traitors’. Two of the earl’s principal tenants, his doctor and solicitor, led a large meeting in Mohill where seventy farmers signed a letter of condolence and noted that, ‘No man did more for his tenantry than Lord Leitrim did. His chief aim was for their welfare’.

On the Saturday following Lord Leitrim’s funeral, The Irish Times published a letter from ‘A Tenant-Farmer’ from Mohill (not a tenant of Lord Leitrim). The writer noted that the earl was a resident landlord who gave employment to hundreds of workmen. The average wage bill for Lough Rynn was, he wrote, £80 per week and ‘many a poor tenant . . . earned not only his rent during the winter months, but also what kept himself and his family in comparative comfort’. While acknowledging Lord Leitrim’s many faults, and that much of peace and prosperity on the estate was brought about by ‘harsh measures and by ruling with a rod of iron’, Lord Leitrim’s labourers had, he said ‘fair regular wages, neat cottages, each a cow’s grass, and their children educated and clothed at Lord’ Leitrim’s expense’. He wrote: ‘Whatever firebrands may say of it, the tenants on the estate are now better housed, better clad, have more stock, are richer, and their lands better laid out and better cultivated’ He also claimed that the earl’s rents were far from being rack rents, and having ‘known the property upwards of 50 years . . . it is in the hands of a peaceful and prosperous tenantry’.

Most of the people of Lough Rynn at least seemed to be at one in mourning the twenty-three year old John Makim who had only recently moved to Milford from Rynn. His funeral cortège was met outside Mohill by a ‘vast number’ of tenantry and estate employees, and shops closed until the ‘beautiful, solemn burial service’ was concluded.