Lord Leitrim and love: Part 2 Romance

Part of a series of articles published in the Leitrim Observer in summer 2020.

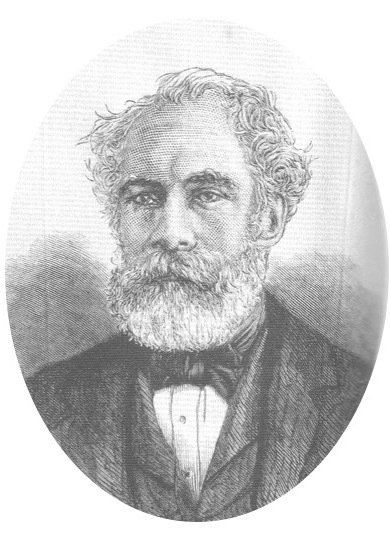

This article looks at the romantic exploits and relationships of William Sydney Clements, 3rd Earl of Leitrim, Lord Leitrim.

(Part 1 looks at the Earl’s formative years and family relationships.)

Lord Leitrim and women

While the allegations can neither be proved nor disproved, there are no indicators that the earl had sexual relationships with local women. Indeed the contemporary stories of ill-treatment of women were hardly known around Lough Rynn, and were largely limited to the Donegal estates where he had a much more fractious relationship with tenants. One journalist investigating the earl’s assassination in 1878 wrote: ‘even among those who hold the strongest views upon Lord Leitrim’s conduct as a landlord, the charge [of debauchery] is discredited and I did not meet a single person who regarded it as tenable’.

Never married

Lord Leitrim never married, but not because he hated women. Strange as it may seem, as he reached marriageable age, he lacked the confidence to engage with women and felt unattractive to them. As importantly, he lacked the security of income that he felt necessary to offer himself as a suitor. As a second son, Sydney had no real authority or focus until he took over the management of the Lough Rynn estate on the death of his brother Robert in 1839. By that time, he was 33 years of age. Even then, he had to wait until he was 48 to inherit the earldom and gain full control over his income and estates.

First love

Sydney’s first romantic love was his cousin, Lady Emily Caulfeild. Sydney and Emily has spent much time together as children, and a tentative romance blossomed after Sydney went away to school. Sadly, the relationship was doomed: in December 1829, aged 21, Lady Emily died from what was probably tuberculosis. She retained a place in Sydney’s heart for the rest of his life, and decades after her death, he made significant efforts to secure mementoes and portraits of her from his aunt’s estate. Sydney’s tragedies continued the following year, with his mother suffering serious mental illness and being isolated at Killadoon; and he himself suffering a leg injury from which he never fully recovered.

Lady Jane

Having had to resign from the army due to his injury, Sydney accepted a position as aide-de-camp to the lord lieutenant in Dublin. From 1831, he enjoyed an active social life ‘stealing the hearts of the fair ones’ in drawing rooms across the city.

It was not until was he approaching 30 that Sydney had his next serious romance. In summer 1835, he became involved with Lady Jane Parsons of Birr Castle. Unfortunately, things did not run smoothly and the attraction seems to have been one-sided. In July, Sydney packed this bags and headed to Europe ‘because I have nothing but disappointments at home.’

Wondrous free and easy

On tour in Europe, Sydney decided to concentrate for a while on women who, in his own words, were ‘wondrous free and easy’. In Florence, he fell in love with ‘more than one young lady’ – which had the desired effect. He wrote: ‘I got up my spirits again, and when I lose them again, it shall not be for a woman’.

By the start of 1836, Sydney was in Rome and having an affair with the ‘provokingly pretty’ Marchesa di Francavilla, and settled into a ‘comfortable’ exchange. It appears that the Marchesa became pregnant. Within months, she was facing a ‘long confinement’ and had been removed to a convent. Sydney reflected, ‘if I am not stabbed before I leave Rome, I suppose I may think myself lucky’. He left Rome on April 14th without ever seeing his ‘poor dear Marchesa’ again.

Mary Woolley Gibbings

It wasn’t until 1838, when he was 32, that Sydney reconsidered marriage. In February, the Freeman’s Journal announced that Sydney was ‘soon to be allied’ to ‘a lady of vast possessions’, the 39 year old Mary Woolley Gibbings of Cork. Mary was educated and informed and accomplished in drawing, music, science, chemistry, and six languages. Unfortunately the marriage was postponed in March after Sydney’s brother George died. It was never revived, and later that year, Mary married Viscount Combermere as his third wife.

Taking over Lough Rynn

The ill-fated relationship with Miss Gibbings seems to have dissuaded Sydney from any romantic involvement for the next few years. As did the death of his brother Robert the following year.

He turned his attentions to Lough Rynn, and from the early 1840s, was preoccupied by the estates and the impact of the Famine. His sister, Lady Elizabeth urged him to find a ‘an eligible and suitable companion’ to turn his house into a comfortable home. But Sydney largely kept to himself when he was at Lough Rynn, restricting his circle to a few close friends and local acquaintances.

It took a decade before he acted on his sister’s advice and considered marriage again. In 1848, ‘after all the toil and labour’ of the Famine years, Sydney informed his father that ‘it is most desirable for my happiness that I should marry’.

At 42, Sydney met a Miss Stuart, and declared that he was ‘caught at last’. All seemed to be going well until Sydney cried off. Still dependent on his father for funds, Sydney felt it impossible to enter into marriage without the security of a sufficient income to maintain a family. His father was not happy, but Sydney was resolute about feeling ‘obliged to resign a connection which is in every respect most desirable and one which you would not fail to like’.

Rachel Irby

Six further years passed before Sydney, then 48, seriously considered marriage for the last time. The ‘cheerful and pleasant’ Rachel Irby was the eldest daughter of an old friend. Although she had no fortune, it appeared that Miss Irby’s feelings were not in doubt. His sister Elizabeth reported that Rachel spoke of Sydney ‘with the greatest of pleasure and affection’ and was looking forward to coming to Ireland.

Although the engagement was announced in the newspapers, Sydney again cried off, and again cited issues over income and money. His sister remonstrated him, writing that Miss Irby was ‘considered to be a fortune in herself’ and that he was ‘a very fortunate man in having engaged her affections’. She finished: ‘Your part should have been to lay yourself and your fortune at her feet’. There was to be no reconciliation and Sydney returned to his lone life at Lough Rynn.

J

As time passed, there are a number of references to relationships in Sydney’s diaries but nothing that approached a serious alliance. Around 1864/65, he wrote of a woman called ‘J’ who lived in London and who gave birth to a girl on 29 December 1864. Sydney was concerned for the child’s and J’s health, so much so that he wrote to Dr Soden in Mohill for a second opinion. Soden hurried to London but by mid-February things had settled, and Sydney reported that he had met J in the park and that Soden was on his way home.

Anne Fleming

Separate to his efforts to secure a marriage to a ‘suitable’ wife, there is evidence that Sydney had a long relationship with his housekeeper at Killadoon. Anne Fleming was a ‘very handsome, dark, woman of few words and her relationship with Lord Leitrim lasted from as early as 1845 until the earl’s death in 1878.

The family seemed to be aware, not only of the relationship with Anne, but also of the connection between the earl and Anne’s son, William Kincaid. Kincaid had entered service at Lough Rynn in 1858, around the age of 12. After the assassination, Lord Leitrim’s brother-in-law noted on a newspaper sketch of Kincaid that he was, ‘Lord Leitrim’s groom and usual attendant wherever he went; very like him’. The earl left Anne £1,000 in his will, and £200 to William Kincaid, significantly more than other servants received.