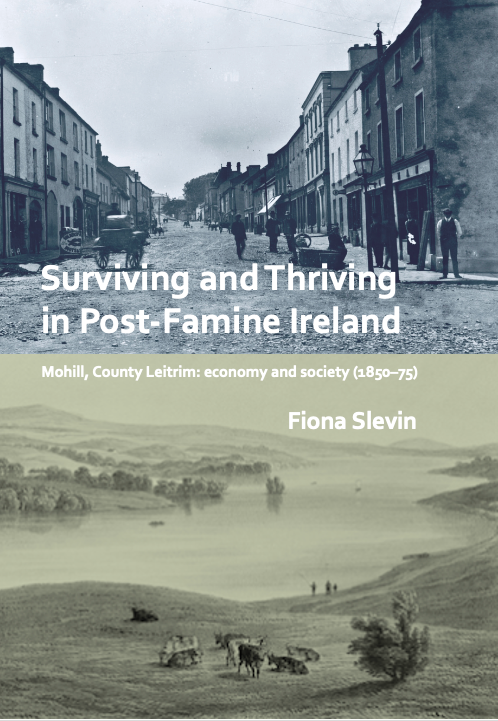

About the thesis

Despite the death, disease, displacement caused by the Great Famine, in the following decades, Mohill experienced economic growth and even prosperity. Agricultural prices increased, a retail sector developed, and new opportunities opened for a growing middle-class.

The thesis investigates the market dynamics that underpinned local economic growth. Drawing on a wide range of primary sources, the study systematically tracks the flow of money between sectors of the economy. In doing so, it assesses farm viability, consumerism, shop credit, household income, emigrant remittances, and the role of government and finance in driving local commerce.

The study demonstrates the vitality, ambition and entrepreneurship present in rural Ireland in the aftermath of the Famine. Overall, the research demonstrates the importance of rural towns and their hinterlands in the economic and social development of post-Famine Ireland, and particularly highlights the significant work, agency and economic contribution of women in the period.

Read the Prologue to the book below.

Download as a pdf for free or buy in book form.

Prologue

Mohill, County Leitrim, February 1873

On a Saturday in early February 1873, the shopkeepers in the town of Mohill, County Leitrim opened their doors in the hope of a few customers with money to spend, or even better, with cash to pay towards their credit bills. The weather, always a common topic, had been dreadful for months, and the long, wet, ‘uncommonly cruel’ winter had continued into February with vicious cold winds from the north-east. Although locals had spent a bit of money at Christmas on special foods like currants and whiskey and on luxuries like earrings and new crockery, it was proving to be a long few weeks before people had surplus cash in their pockets. This year, local people were holding on to what money they had for fear of ‘scanty crops’ and high prices. Even the weekly Thursday market had not brought in customers. Farmers and shopkeepers alike could only hope for an upturn in business at the Monaghan Day fair at the end of February. Monaghan Day was the biggest fair of the year in Mohill, when farmers and dealers with money to spend travelled to Mohill from far and near to buy and sell cattle.

But that was still a few weeks away. Since Christmas, few customers had come in to Thomas Ward’s new drapery shop to buy a waterproof coat or boots, or a new cashmere shawl. At least the workhouse had paid him for the porter’s new suit, even if Mr Cull had won the last tender by under-cutting Ward’s price by five shillings. The farmers, normally the mainstay of Ward’s business, were largely absent, and small farmers especially would have to rely on earning cash from sales of eggs and butter, or some income from knitting or sewing to tide them over until circumstances and the weather improved. Thankfully, the next gale day for paying rent to the big landlords like Lord Leitrim, was some months away. But people still had to get through the next weeks. For small farmers, there were few ways to access capital or loans, and there was little likelihood of getting an advance from the local bank; a few might be lucky enough to receive a remittance from an emigrant family member. For some, their situation was bad enough to drive them to seek outdoor relief from the workhouse, and demand for such relief increased by 15% in the few weeks between the end of January and mid-February. Some may have taken action to emigrate, and considered the offer of free passage to Queensland for labourers and domestic servants advertised by Hugh Ross in Mohill. One of the few to be grateful for the dire weather might have been Mr John McGavern, the constabulary sub-inspector in Mohill, who had reason to hope that the rain and wind would constrain the levels of petty crime and public drunkenness that kept his sixty-four men busy across the union.

For Thomas Ward, it seemed that the only people with money to spend were salaried employees and a few fellow traders and bigger farmers, especially the workhouse suppliers who had been paid in the past weeks. Unusually, most of the customers who did drop in to Ward’s shop put cash on the counter to pay off some of their credit bills rather than just buying more goods on credit. Mrs Crowe, one of Ward’s earliest customers, dropped in that Saturday; as one of the workhouse’s contractors, she had been paid in January. Mrs Crowe may have run into Mrs Anne Burbidge, the nurse at Mohill fever hospital and one of Ward’s best customers: Mrs Burbidge spent money a few times that week, perhaps treating herself after the Mohill board of guardians gave her permission to have her two children reside with her in the hospital. Ward may have been thankful for the amount of business that the workhouse sent the way of local shopkeepers and farmers: Michael McGarry, the top supplier to the workhouse, had run up a significant bill of more than £3 10s in the previous three months; that Saturday, he came in and spent another £2 19s 9d, but thankfully, paid Ward a welcome £6 6s 5d in cash.

Being a Saturday, the board of guardians of Mohill Union and workhouse were in town for their regular meeting. The agenda was fairly light that week; there were the usual issues over a coal contract, the quality of meat, and insufficient milk being delivered, but an official inspection reported that the workhouse was generally in good order; the guardians also discussed a proposal to address flooding of the Shannon river. Memories of the smallpox epidemic of the previous two years had receded, but the guardians were still accounting for the compulsory vaccination of children in the union, and they were still dealing with a claim for a suit of clothes that had belonged to a young man who had died from smallpox. Although there were only about 200 inmates in a workhouse designed for 700, nearly one quarter were in the fever hospital, which may have made the guardians more disposed to respond positively to Mrs Burbidge’s request to have her children live with her.

Since many of the guardians had to travel some distance – the chairman, the Earl of Granard lived over twenty kilometres away – some of the local businesses might have hoped to benefit from their custom. The guardians who were members of the Protestant church may have attended a crowded ‘annual soiree’ the night before and met with some of the local shopkeepers like Mr Hayes and Mr Turner, or had a word with Sub-Inspector McGavern. Messrs McGavern and Hayes had led proceedings at the gathering, which included recitations that scorned alcohol and a talk on the destructive effects of fiction; the ladies had provided tea.

Although none of the guardians did business with Thomas Ward that Saturday, some might have stayed to eat at Mrs Little’s hotel or spent money in one of the other shops that lined the Mohill streets. Anyone who ventured into town that day could have visited the apothecary for a tincture for their cough or acquired a new hat or a silk scarf in Thomas Hayes’ shop; they might have picked up some ginger biscuits and coffee at John O’Donnell’s grocery shop, or accomplished several errands at David Noble’s general store, perhaps buying a bottle of Kinahan’s whiskey or a new padlock. They could have considered stopping at Elizabeth Turner’s shop for some Belleek china, or gone around the corner to her husband’s premises to pick up the local newspaper, and if they had the notion, could have spent up to five shillings on a Valentine card for their loved one.