Valentine's Day in 19th century Ireland

Origins

It is easy to think of Valentine’s Day as a uniquely modern phenomenon. But it has been around for centuries, with origins that can be traced back to the Roman fertility festival of Lupercalia. In the 5th century, the Christian church claimed the festival, and 14 February became St Valentine's Day.

The feast became associated with romantic love in 15th century France, and the first known Valentine note was written by the Duc d’Orléans to his wife from his prison cell in the Tower of London. It took until the 1790s for a commercial market and pre-printed Valentine cards to emerge, and by the mid-1800s, Valentine cards were hugely popular. They became even more so with the introduction of the Penny Black stamp and more affordable postage rates. In 1841, some 400,000 valentines were posted throughout England.*

What may be more surprising is that they were also popular in Ireland.

Love's Lottery

It seems that Valentine’s Day was observed in Ireland in the early 1800s. In January 1816, the Freeman's Journal advertised a lottery of 20,000 tickets and a prize fund of 50,000 guineas in gold. The lottery was to take place on Valentine's Day, 'a day rendered as remarkable in Lottery concerns, as for the partialities that are then usually communicated in Poetic Lays'.

On 9 February, the paper published a poem to encourage the purchase of tickets. Its sentiments are remarkably timeless.

VALENTINE’S DAY,

Or the best Present for the Ladies.

_________________

Now Valentine's Day is returning,

And sweetly the mild Zephyr blows;

Now the furnace of Cupid is burning,

In the breasts of the Belles and the Beaus.

One offers a Ring or a Jewel,

For the Finger or Neck of his Fair;

Though if she’s inclined to be cruel,

Such Gifts will not cure his despair,

But I'll shew you the method to nick it,

And the Damsel will soften her frown;

Enclose her a Lottery ticket,

And purchase the present from BROWNE.

For, trust me, ‘twill prove more unfailing,

Than your nonsense of Sonnets and Sighs;

No argument half so prevailing,

As the sight of a CAPITAL PRIZE.

The patron saint of true lovers and cheap stationers

By 1850, a columnist at the Connaught Telegraph felt that the pressures around Valentine’s day were getting all too much. On 20 February they concluded that ’St Valentine is the patron saint of true lovers and cheap stationers, and he and his day (the 14th of February) are held in the greatest dread by nervous old gentlemen, irascible parents and guardians, confirmed bachelors, and over-worked postmen’.

Valentine’s Day in Leitrim, 1858

The mid-1800s in Ireland were of course dominated by the Great Famine. Counties like Leitrim were decimated through disease, death and emigration. After 1850, when the worst of the Famine had abated, thousands continued to emigrate from Leitrim, and the majority of those who remained eked out a living as labourers and servants, with low wages, little security and few prospects.

Despite this, County Leitrim was transformed and a new middle class of tenant farmers, landholders, professionals and merchants emerged. Confidence was growing and Mohill town was lined with shops and traders. Local newspapers carried advertisements for goods like coffee, whiskey, dentistry, coats, perfumes, clocks and watches.

In January and February each year, ads would appear for Valentine cards.

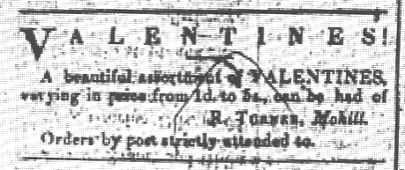

A beautiful assortment of VALENTINES

An ad in the Leitrim Gazette, published in Mohill through January and early February 1858 offers a 'beautiful assortment' of Valentines for sale in Robert Turner's shop, or by post. They range in price from one penny to five shillings.

So who bought them? We may never know. The very notion of ordinary men and women exchanging Valentine cards is contrary to our common understanding of living standards in the aftermath of the Famine. We know that men labouring at work like spreading manure or planting potatoes might earn 8 or 10d a day, so would have to work an hour to buy the cheapest card; they would have had to hand over a week’s wages to buy a 5 shilling card. The cards would certainly have been more affordable for a schoolmaster or schoolmistress, or a carpenter or clerk earning £20 to £50 a year. Or maybe they were bought by the few doctors, attorneys, and gentry who lived in the area.

Perhaps Valentine’s Day offered some light relief from the ever-present disturbances and tensions over land. Turner’s ad on 30 January appears on the front page of the newspaper alongside articles about tenant rights and a ‘great meeting at Milford’ between Lord Leitrim and his tenants. The same front page includes a report from the recent Petty Sessions in Mohill, where a number of people were convicted for ‘tippling in a shebeen-house'. The offenders were fined 5s each. Their illicit whiskey cost them the price of a high-end Valentine card.

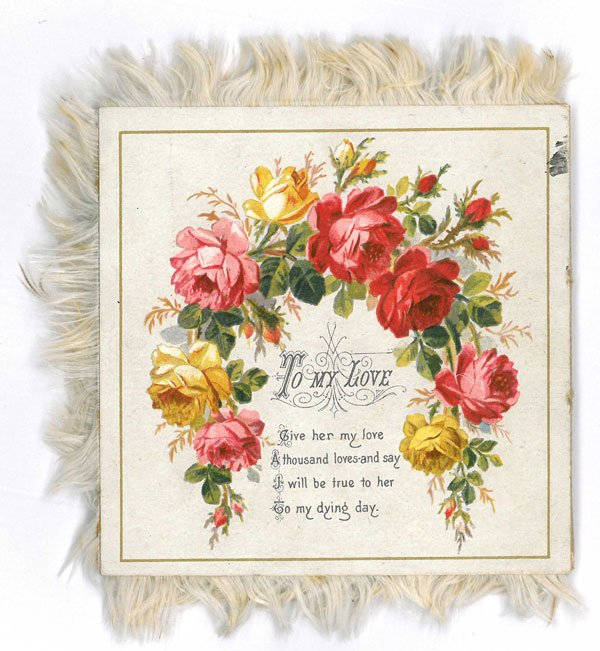

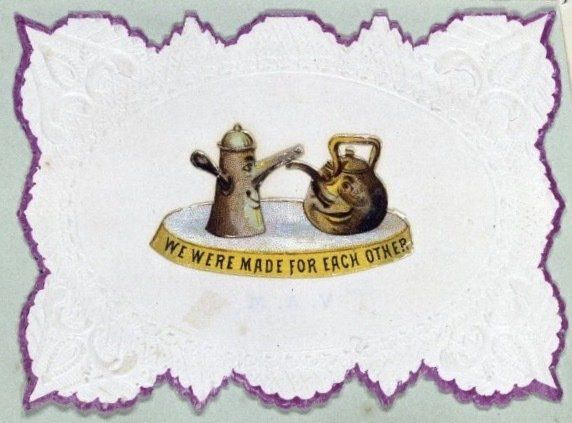

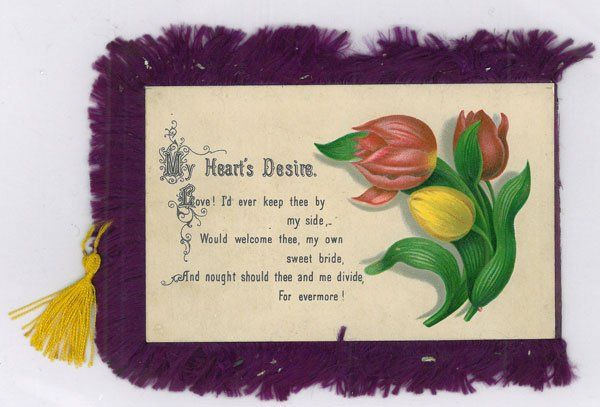

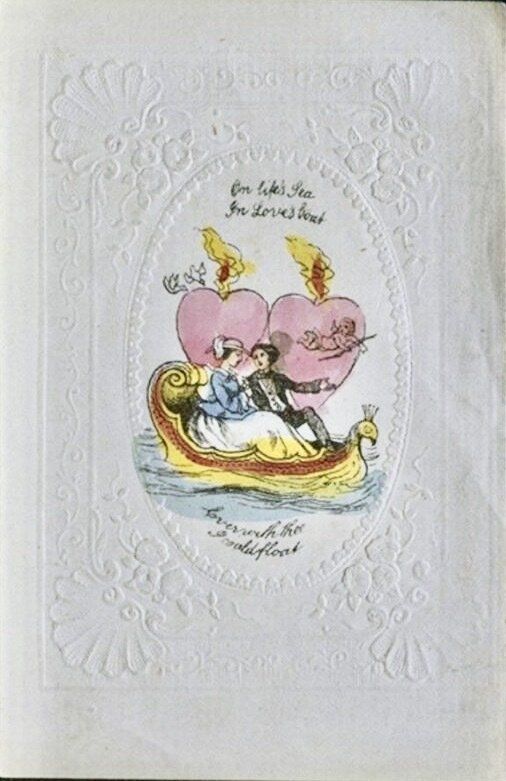

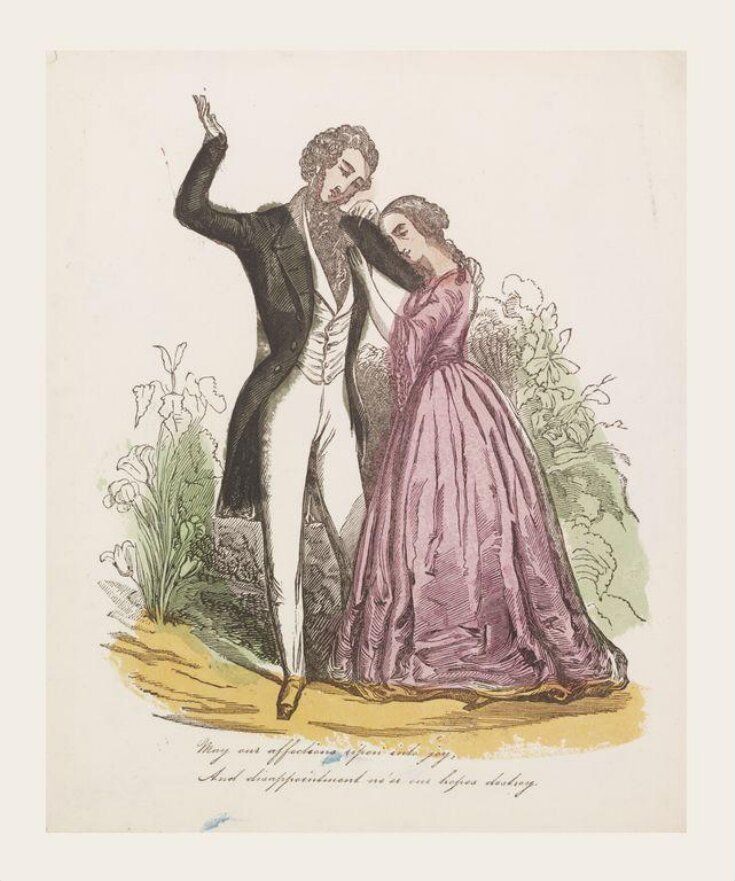

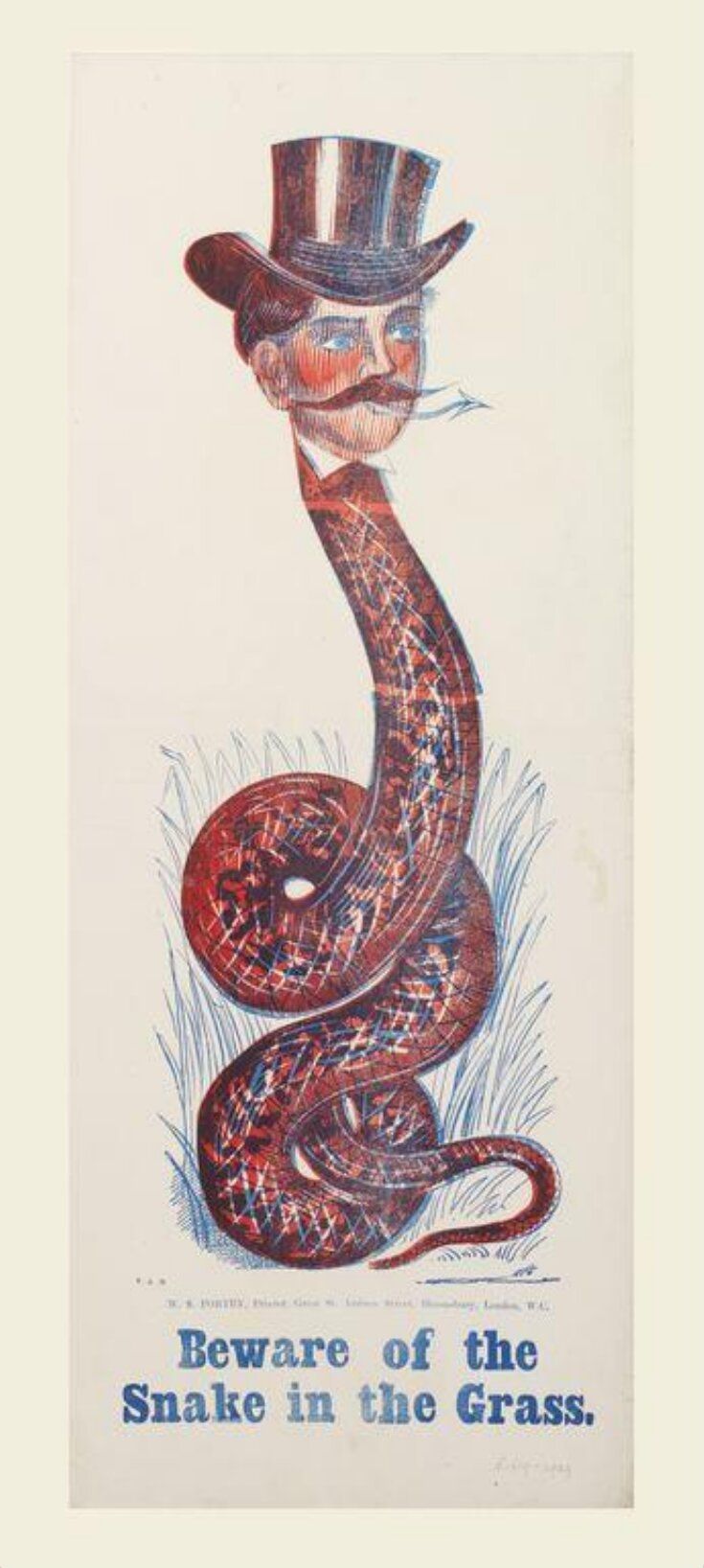

The cards

What did these cards look like? We cannot tell. We can only assume that they were similar to the cards that were on sale in Britain. The simple ones, and presumably the cheaper ones, were printed cards with messages that would not be unfamiliar today. Some were humorous, some were rude. The more expensive ones might have been handmade lace confections with appliqué flowers, or hand-painted images.

Valentine's Day during the Famine

If the discovery that the good people of Mohill were exchanging Valentine cards in 1858 was surprising, even more remarkable may be the continued posting of ads for Valentine cards through the worst years of the Famine.

By early 1847, it was clear that the failure of the potato crop was having a severe impact on those who relied on it for food. The Famine had taken hold. On 12 February 1847, William Smith O'Brien told Parliament about the destitution, starvation and death that was visible from Bantry to Killybegs.** But newspapers across the country, including in areas where the toll was high, continued to carry advertisements for Valentine cards.

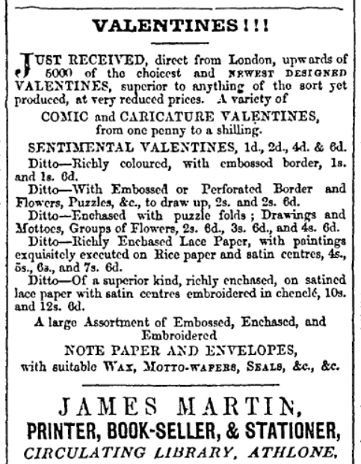

Through January and February of 1847, 1848 and 1849, local shops advertised 'a great variety of beautiful Valentines' in newspapers from the Anglo-Celt in Cavan to the Kerry Evening Post and Kerry Examiner in Tralee and the Westmeath Independent in Athlone. On 12 February 1848, James Martin of Athlone proclaimed the arrival of ‘upwards of 5000’ valentines, and advertised a wide range of cards, from comic to sentimental. They ranged in price from one penny to 12s6d for a 'superior kind' on ‘satined lace paper’ with embroidered centres.

On 4 February 1848, Guy’s of Patrick Street, Cork advertised their 'choice collection' of Valentines in the Irish Examiner. The same page carried an account of the ‘heart-rending and disgusting’ situation at Macroom workhouse that approached ‘murder by starvation'. The workhouse was full and nearly all outside it were ‘starving for want of relief’, while the ‘desperate wretch who has crawled ten or twelve miles in search of a morsel of bread’ was turned away.

The reality is that not every section of the population was affected equally by the Famine. Many of those who lived through it continued to live their lives as shopkeepers, tradespeople, farmers, doctors and public servants. It its aftermath, a significant proportion experienced greater prosperity and sustained development. And many of them were able to subscribe to little luxuries like Valentine cards.

Another Irish connection

In 1835 an Irish Carmelite, John Spratt was given the remains of St Valentine by Pope Gregory XVI. He brought them back to

Whitefriar Street Church, Dublin where they still reside.

More reading

Whitefriar Street Church, Dublin and the Shrine of St Valentine

Valentine’s Day in the Victorian Era, from Five Minute History

A history of Valentine’s Day celebrations – from fertility festivals to the first cards, from BBC History Extra

The Heart of the Matter: A History of Valentine Cards from the Collections of The Strong National Museum of Play, Rochester, New York

References

* Valentine’s Day in the Victorian Era, from Five Minute History

** Hansard 12 February 1847 vol 89. Famine in Ireland.

Get in touch

There has been little research on towns like Mohill and little is known about how they turned into thriving towns in the latter half of the 19th century. If anyone has original records that relate to shops, trades and professions from 1850-1875, especially ledgers, sales and order books, letters, photos, etc, please get in touch using the

contact form here

A version of this article was published in the Leitrim Observer, 9 February 2022.